Breast Relief: New Approaches to an Old Problem

February 19, 2021

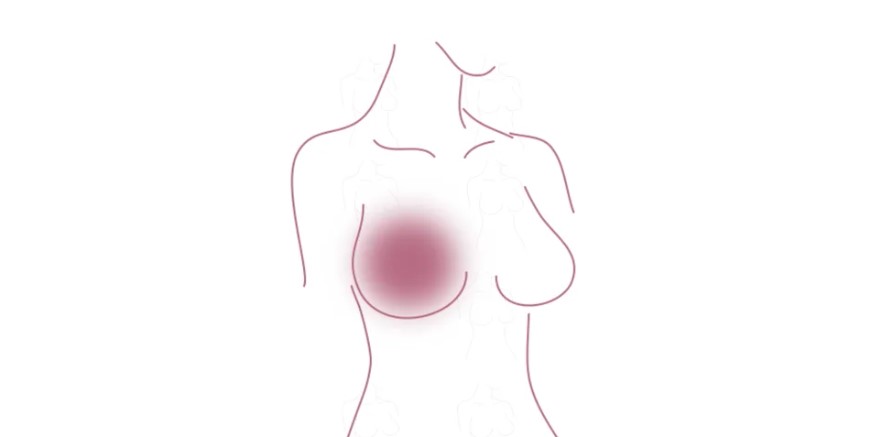

Breast cancer affects one in eight women across the United States. What is often overlooked is that a significant percentage of those women will go on to develop Post-Mastectomy Pain Syndrome (PMPS), a chronic pain after mastectomy that can persist in the breast, chest, and underarm areas for years.

We believe that surgery can affect the sensory nerves in the breast and is chest the driving force behind this condition. These nerves are often disturbed as part of standard mastectomy techniques. It is difficult to manage the repercussions of nerve damage in the chest, breast, and axillary (armpit) areas. Our experience has taught us that appropriate nerve handling during the mastectomy may avoid the problem completely. Nerve pain diagnosis, treatment, and prevention may be under-addressed in the breast.

That’s why we developed Breast Relief, a unique, multidisciplinary clinical and research initiative that aims to address and prevent PMPS. This month, we launch a new site dedicated to this topic. Read on for some background on what we know now.

PMPS is not a new discovery.

PMPS was first described in 1978. At that time, when breast cancer treatment was focused on survival rather than quality of life, it was considered acceptable.

Breast Relief aims to shift paradigms in surgical breast cancer treatment by diagnosing patients, systematically treating them, and educating healthcare and patient communities on long-term pain.

Neuropathic pain is a key diagnostic criterion.

Neuropathic pain comes from damage to the nerve. Patients frequently describe the sensation as burning, itching, or “electric shocks.”

Most diagnostic criteria describe PMPS as neuropathic pain of at least moderate severity in the breast, underarm, or arm area that has persisted for at least six months and may worsen with shoulder movement. While this set of criteria varies by paper and research institution, neuropathic pain is a consistently essential component.

Some diagnostic criteria recommend that the condition be renamed Post-Breast Surgery Pain Syndrome, since it can afflict patients who have undergone breast conservation therapy and cosmetic breast procedures.

Incidence appears high.

We estimate that PMPS may affect up to 20-70% of women who have undergone breast surgery. Some research points to a lower 8-9%. What we do know is that it can persist for many years, and it fluctuates with time in many patients.

Age, BMI, and psychological conditions could be risk factors.

Evidence suggests that younger patients have a higher chance of developing PMPS. This may be due to the fact that these patients often have higher grade tumors that require more aggressive therapies. Some research also indicates that mood disorders—like anxiety and depression—and BMI may relate to PMPS. Patients who report higher levels of pain immediately following surgery have the highest risk of developing a chronic issue.

It’s been linked to some surgical techniques.

Complete axillary lymph node dissection is associated with greater PMPS development risk than sentinel lymph node biopsy. Radiation has also been linked to the condition. Breast Conservation Therapy may carry more PMPS risk than mastectomy, even controlling for radiation. There is no clear set of studies that show that any specific type of reconstruction is associated with more or less pain.

Nerve protection is the most consistently successful prevention method.

Nerve preservation improves outcomes. In some cases, proper nerve handling can avoid the problem altogether. For example, when breast surgeons are protective of nerves in the armpit area during an axillary lymph node dissection there’s much less incidence of PMPS. There are many other nerves in the chest breast area that we believe should be protected or managed appropriately if they cannot be preserved.

The new Breast Relief website details our treatment approach, which can include pain management, physical therapy, regional anesthesia, and—for some patients—surgical interventions. Check out the site to learn more about what we can do to prevent and mitigate this chronic pain condition.

Nuances in Anatomy of the Back and Flank Region by Gender: Published Findings

Better late than never – this week we finally published an article that was written several years ago, the principles of which I have been…